For humankind, holiness is found in learning to become fully human. Jesus’ incarnation is our example of becoming fully human, fully holy.

- Discussion Outline

- Discussion Audio (1h13minutes)

- Text: Mark 2:13-28

The stories Mark includes in the passage that we discussed today asks the question, what is genuine holiness? The scribes and Pharisees had one response to the question. Jesus demonstrated something quite different from the understanding of the former. What we see is Jesus restoring people to full humanity and full equality. We see an allusion to the Creation account to recover the true meaning of holiness.

When we read the gospel accounts we most often identify with the disciples and followers of Jesus, because as Christians, we are. We do mention and talk about how we shouldn’t become like the Pharisees of old, but we view them mostly as ancient-day equivalents of groups today that oppose Christians. This is unfortunate because modern Christianity, especially American Christianity, bears far more parallels with the Pharisees than we’d like to think.

When Jesus walked the earth and when the gospels were written down, Christianity was an oppressed and marginalized religion. Its adherents were, at least at times, considered criminals. Even in the best of times they were looked upon with suspicion for their rejection of Empire.

Call of Levi

Jesus calls a tax-farmer, a tax-collector, to follow him. Tax-collectors were considered traitors to the Jewish nation, a collaborator with the enemy. They were seen as even less than lepers – there were provisions for lepers to attend synagogue, but tax collectors were excluded completely. If Levi was collecting fish taxes from the fishermen, what did Simon, Andrew, James, and John think when Jesus gave the invitation?

Levi is a collaborator. A true freedom-fighter would have nothing to do with such a weasel, except perhaps to murder him as an enemy of the revolution.[1]

As with earlier accounts, there is no mention of confession of sins and wrongdoing; there is no mention of repentance.[2] Levi simply follows. Jesus does not require a confession or declaration of repentance before he allows a person to follow and be a disciple. The person’s actions declare far more than mere words from mouths. Levi certainly turns away from his past, but his past is not the focus. There is no dwelling on past sins, on remorse, or even restitution. The focus is on following Jesus. This continues Mark’s vision of repentance.

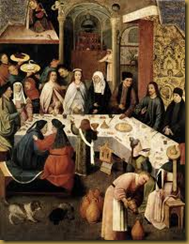

The Feast

The story abruptly transitions to a banquet setting. According to Luke, this feast was hosted by Levi in his home. But Mark leaves the setting ambiguous and the language used lends greater weight to the feast being hosted by Jesus in his home.[3]

Middle Eastern banquets are not strictly private affairs. To show the generosity and graciousness of the host, all in town are tacitly invited and allowed to attend.[4] Thus Mark shows that Jesus invites everyone to his “Messianic banquet.” The scandal is not so much in who is invited but who shares the seats of honor with Jesus around the banquet table.

Jesus allows the tax-collectors and “sinners”[5] to share the table with him. He eats from the same plates and drinks from the same cup as they! Jesus associates with the unclean! A “holy person” is deliberately choosing to associate with the “unholy.”

To go and sit down at that table and to enter into fellowship with this group would violate their idea of “holiness.” For them, Bible and tradition drew clear boundaries around who and what was “pure” and “ritually clean.” Holiness was performed out of love and respect for God, using proscribed sets of rituals that were carefully passed down through tradition. The “righteous” remembered the grace that God extended to them. In return, they performed the rituals and abided by the major divine laws for conduct and behavior.[6]

… The complaint is that Jesus sets a bad example as a holy man by welcoming known sinners into his circle. In the minds of these critics, Jesus should have disassociated himself publicly from such sinners and should have summoned them to repentance and study of the religious law as a precondition for any social acceptance. These critics were desirous of upholding a religious standard and of chastening and perhaps reforming transgressors.[7]

The big issue the scribes and Pharisees had with Jesus is that he allowed table fellowship without first requiring visible “repentance” from the “sinners.” Jesus was saying, “Come to me, share a meal, and repentance will naturally follow.” Jesus didn’t draw boundaries. All are invited. But he allows people who are uncomfortable with the kind of people he associated to draw themselves out of his circle. In other words, people bring judgment upon themselves. People decide for themselves whether they are in or out.

Those who want to be insiders in Jesus' group must envision themselves reclining next to people whose politics and behavior they find disgusting, and eating out of the same dish with them…[9]

Weddings and Fasting Don’t Mix

The banquet motif continues with this next incident where Jesus is asked why his disciples don’t fast. In response Jesus tells his questioners that it is inappropriate and rude to the host to fast during a wedding feast.

The traditions of the Pharisees designated Mondays and Thursdays each week as days to fast. They did this to express remorse for the past sins of the nation, for repentance for current sins, to express piety, and to look forward to the coming of the Messiah. Disciples of John the Baptist fasted for probably these same reasons. The Baptist had proclaimed the nearness of the Kingdom and thus it would have made perfect sense to express piety in anticipation of the coming.

The puzzlement of those who questioned Jesus on this issue was caused by the fact that Jesus proclaimed the near arrival of the kingdom of God, the day of salvation, but was not showing what his critics regarded as proper preparation by mourning over its delay.[10]

For the Pharisees and the disciples of John the Baptist, repentance and holiness were symbolized through self-denial. Once again Mark shows that both of these concepts were demonstrated quite differently in the actions of Jesus. Two vastly different visions of holiness are on display. Through two parables – the garment-patch and the wine-wineskins – Jesus conveys the message that holiness according to the law is obsolete. The new has come. The old must pass away, or it must adapt.

Lord of the Sabbath

In response Jesus alludes to a story of David when he “breaks” the Law regarding scared food. This Davidic incident takes place while he is running from Saul, the anointed king of God. In doing so Jesus identifies himself as the leader of fugitives. Jesus defends the actions of his disciples. Note that the disciples did not ask Jesus first or get his permission before “harvesting.” Rather they do so, and in response to accusations, Jesus defends them.

Jesus casts his lot with the oppressed and the marginalized. The Sabbath commandment in both Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5 is given to remind the Hebrews that all humankind was created equal and deserve a time to rest. On the Sabbath people are commanded to relate to one another as equals. It doesn’t matter that outside of the Sabbath one is master and another slave, male and female, citizen and non-citizen, parent and child – on the Sabbath power, privilege, hierarchies, and authorities must be subordinated to equality (c.f., Galatians 3:28).

The Sabbath is a reminder that all humankind was created in the image of God (Genesis 1:27) and that it was very good (Genesis 1:31). When God declares the seventh day holy (Genesis 2:3), I believe it includes all of creation. The day by itself would be meaningless without all that came before and all that it represents. Thus I believe the seventh day represents completeness, perfection, Shalom, and holiness.

Humankind is holy at the end of Creation Week. It is at the Fall that humans become less than human. With the Incarnation, Jesus comes to reverse the Fall and restore humanity to its fullness. Humanity does not become holy by trying to become more like God. Humanity becomes holy by learning to become fully human as was originally intended in Creation. By becoming fully human, the image of God is restored. By becoming fully human, we become the image of God.

It isn’t wrong to want to bear the image of God, but I think for far too long Christianity has taught the wrong means. It has taught holiness that bears much resemblance to the kind of holiness espoused by the Pharisees of old. I believe what we need is to embrace the kind of holiness Jesus demonstrated: that of becoming fully human as God originally intended for us. And part of the gospel is to help those around us become more fully human. If we do not, we risk missing Jesus just as the Pharisees missed him. We can be so sincere in holding onto beliefs we are convinced are right that we miss Truth.

Jesus is Lord of the Sabbath because he chose to fully embrace humanity and taught his followers to do the same.

To side with Jesus will mean for the audience of the Gospel the loss of any claim to righteousness, the loss of the prerogative of avoiding unpleasant people, and the loss of absolute certainty about biblical interpretation.[12]

[1] Reading Mark: 2:13-14.

[2] Feasting: Mark, location 2665.

[3] NICNT: Mark, 2:17.

[4] Bailey, Kenneth E. Jesus Through Middle Eastern Eyes, p. 246, footnote 15.

[5] NICNT: Mark, 2:15-16. “The term is technical in this context for a class of people who were regarded by the Pharisees as inferior because they showed no interest in the scribal tradition.”

[6] Feasting: Mark, location 2676.

[7] UBC: Mark, 2:13-17.

[8] UBC: Mark, 2:16 note.

[9] Reading Mark: 2:15-17.

[10] UBC: Mark, 2:18-22.

[11] UBC: Mark, 2:23-28.

[12] Reading Mark: 2:18-22.